Submission and Peer Review Process

Submissions Guidelines

We welcome various formats of submissions, including poetry, personal narratives, classroom action research, teacher inquiry, and formal academic research that is empirical or conceptual. We encourage submissions from classroom teachers, students, teacher educators, and other scholars of education. Submissions should be no more than 6,000 words (not including the reference list). We recognize that not all submissions will require citations. If your work references the work of others, please continue reading about our approach to citations. Otherwise, scroll further down to learn about our peer review process.

On Citations: Two Guiding Principles for Contributors to The Critical Social Educator

Rather than mandate a standard format or style guide for references and citations, the editorial team at TCSE offers the following guiding principles for writers. Submissions may be offered in any citational format of the writer’s choosing, but here we offer our recommendations and preferences based on our guiding principles.

Citations are political; who we cite, how responsibly we cite, and which claims we believe warrant citations are all political choices that communicate our commitments.

Recognizing the ways in which the ideas of BIPoC thinkers are often stolen, unrecognized, and/or mis- or under-cited, the editorial team at TCSE especially values submissions that honor the work of BIPoC scholars and practitioners by citing these works often, accurately, and completely. We advise writers to diligently trace the lineage of the ideas and claims advanced in their work, and to responsibly recognize that lineage through citations and a helpful and complete reference list.

Citations have three main purposes: to assign credit accurately; to support claims with evidence; and to direct the audience to further readings and supportive resources.

With these purposes in mind, we advise writers to use a style for citations and references that most conveniently allows readers to leverage the power of these cited works. We value open access and ease of support; therefore, a style we strongly recommend is one in which hyperlinks are used throughout the piece to easily direct readers to the cited works. A model of this accessible, helpful citational style through hyperlinking can be found here. We particularly value cited works that are also open access (though we understand these are unfortunately rare). All pieces must also include a reference list, and where possible we suggest hyperlinking references in your lists, as well.

In short, we encourage our writers to treat the work of citations as seriously as they treat all the elements of their writing, and to understand citations and references not just as procedural or logistical, but as deeply political.

Our Peer Review Process

The Critical Social Educator (TCSE) is committed to a peer review process that supports both reviewers and authors in their work to create powerful scholarship for elementary social studies education. This commitment requires a shared responsibility to an open process whereby we critique manuscripts with care in order to lift each other and the field of elementary social studies as a whole.

Our commitment to care for one another and for the field calls out the “privileged irresponsibility” we so often see and experience in academic publishing. First used by Joan Tronto, the idea of privileged irresponsibility refers “to the ways in which the majority group fail to acknowledge the exercise of power, thus maintaining their taken-for-granted positions of privilege.”[1] We maintain that academic publishing’s “blind review” process embodies this privileged irresponsibility in that its ableist language and rules grants unequal power to reviewers and editors. The dominant peer review protects reviewers and editors while leaving authors vulnerable to harm. This system, which dates back to 19th century medical journals, assumes that if reviewer and author names are “known” to each other the system will fail. This assumption is anchored in two problematic ideas: 1) that to produce “good” research and/or publications requires a separation of authors and reviewers, and 2) reviewers and editors are objective to the work they are critiquing.[2] The Critical Social Educator joins a growing movement within academic publishing to resist this system.

We find inspiration in the words of Jasmine Ulmer, Candace Kuby, and Rebecca Christ who, in their recent special issue of Qualitative Inquiry, asked peer reviewers to “write the response as a critical friend who is offering generative ideas on ways to grow the manuscript.”[3] In turning to an open peer review process that takes seriously the commitment to care we can push beyond the harmful traditions of academic publishing and open ourselves and our field to healing and change. In other words, what can we make possible for critical elementary social studies when we shift our publication commitments to collaboration instead of competition?

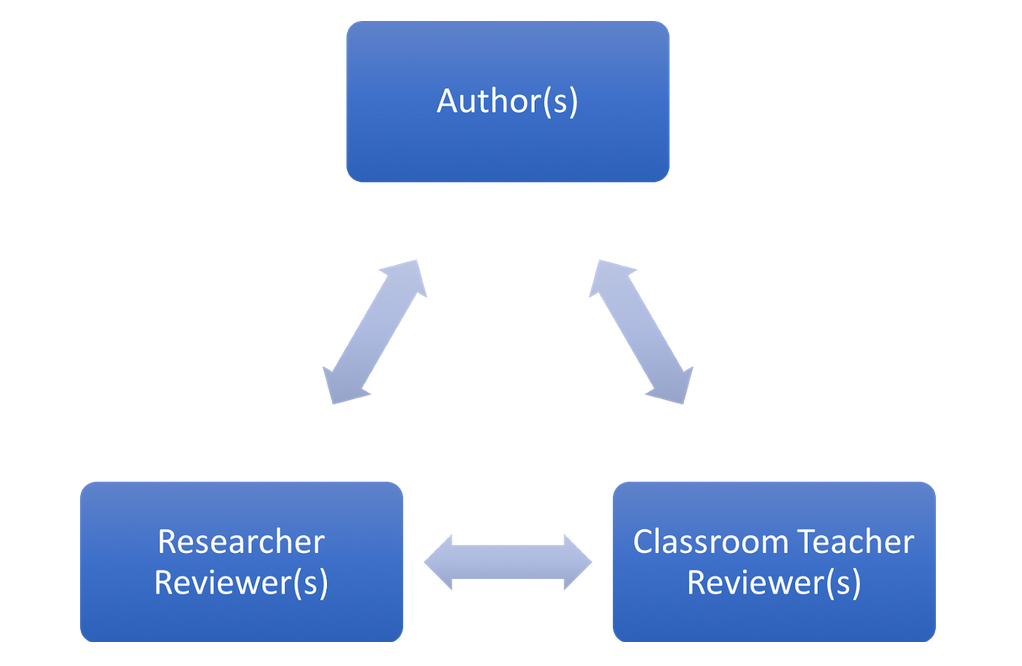

Each manuscript accepted for review at The Critical Social Educator will go through an extensive, open peer-review process. Submitting authors will be paired with both classroom teachers and education scholars to receive feedback on their work. Reviewers will be provided a series of questions to facilitate the reading and feedback loop. In creating feedback groups, we work to promote collegiality and a nurturing publishing environment. These pairing groups also work toward TCSE’s overall goal of bridging the divide between education researchers and classroom practitioners. As such, the publishing outcome of the feedback loop will also include a commentary written by reviewers: In the case of a research article, TCSE’s classroom practitioner reviewers will provide a K-6 perspective, and for practitioner articles, TCSE’s education researcher reviewer will provide a research or teacher education perspective. The article and commentary will be published together for readers to continue engaging in the shared thinking, questioning, dreaming process stated by the author-reviewer group.

The open peer-review loop will take on the following structure:

- Submitted manuscripts receive first reading by editorial staff; editorial staff will notify authors if their manuscripts are accepted for review.

- Manuscripts accepted for review will be paired with 3-4 reviewers and introductions sent to both author(s) and reviewers

- Reviewers will provide feedback to the submitting author(s).

- After receiving feedback, submitting author(s) will work on revisions. Authors and reviewers are strongly encouraged to remain in contact via email during this time to pose/respond to questions.

- Submitting author(s) will share revised manuscript with reviewers to provide any additional feedback. At this time assigned reviewers will also begin work on their commentary.

- Submitting author(s) and commentary author(s) will submit final manuscripts for publication.

Both submitting author(s) and commentary authors(s) will receive detailed instructions with definitive dates based on the original submission date.

Notes

[1] Zembylas, M., Bozalek, V., & Shefer, T. (2014). Tronto’s notion of privileged irresponsibility and the reconceptualisation of care: Implications for critical pedagogies of emotion in higher education. Gender and Education, 26(3), 200-214. The authors cite Tronto’s 1990 paper, “Chilly Racists,” presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association for the foundational definition of “privileged irresponsibility.”

[2] Shear, S.B., Christ, R.C., Kuby, C.R., & Ward, A. (2019). Entanglements With(in) the Review(er) Machine: How Can We (Re)View If We Are B(l)ind(ed)? Presentation given at the American Educational Research Association annual meeting in Toronto, ONT.

[3] Ulmer, J., Kuby, C.R., & Christ, R.C. (In press). Introduction to the special issue. Qualitative Inquiry.